- 1,061

Perfect, thanks! It'll be here Thurs.

Personally, that's not far from my original idea, especially if he tells them they'll need things like a formal annual employee training program, ongoing vulnerability scanning, audit logging, 24/7/365 monitoring and alerting, an IDS/SIEM solution, a written Incident Response Plan, a Patch Management program, etc, etc, etc.

I think the "Insurance Consultant" license (whatever that means) sounds closest to my original intention, which was to walk the business owner through that process without getting in trouble for giving unlicensed (and/or terrible) insurance advice.

It seems that I mostly want to be a MSP/MSSP and probably not sell insurance on the side. I've been working for startups just as they start to scale, spend a year or two there, then they sell or merge with someone else. I've been through I think seven M&A deals since 2017 (another niche I'm pursuing) and it'd be cool to do all of the architecture analysis stuff without the layoffs part.

Who on the insurance side does <technical stuff>, like deciding what's acceptable and what's not? Is it basically a predefined list of major vendors, or does there exist a long process of reviewing network topologies, software versions, firewall rules, password policies, logging configurations, etc., like with other regulatory environments? (Becoming GDPR compliant, for example, was easily a 5-figure process and large companies spent millions.)

At the risk of making another bad analogy, perhaps I'm thinking along a boat surveyor or home inspection kind of line.

The book is a pretty dry read, but it's certainly insightful and will give you a good idea of what you're diving into.

I think going to larger businesses and helping them get in compliance and set up proper controls for their insurance broker is more in your wheelhouse from what you've described. Maybe you can partner with an agent who is pursuing the companies you want to consult for. It would be a win/win, he sets up the insurance, and you help them get all of the proper controls in place. - There's probably more money on the consulting side anyhow.

In terms of who does the technical stuff on the insurance side, it can vary greatly. There's the technical of insurance - actuaries, claims adjusters, product and claims counsel (attorneys), underwriting, policy language, etc etc. Then there's the cybersecurity technical side, which many cyber insurers are bringing in-house. The insurance companies will hire dedicated cybersecurity experts to handle the technicalities associated with that side of their business. Go poke around on LinkedIn and you'll have a pretty good idea of their employee structure.

Some examples:

https://www.coalitioninc.com/coalition-security-services

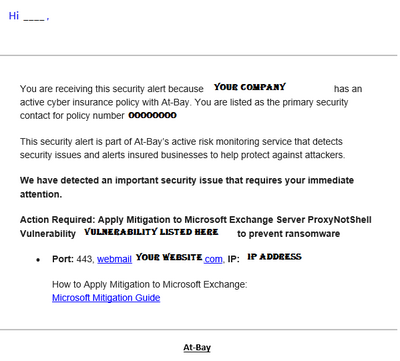

https://www.at-bay.com/security/

The insurers are not going to take great leaps to get a company's cyber risk management up to snuff or be compliant with regulations like GDPR, so there is definitely the opportunity to step into that gap and help those companies out.